Archive

Wage Labor, Capitalism and Communism

Okay, so this is not going to be the usual examination on the topic of wage labor, capitalism or communism. Sometimes when you run into a conceptual brick wall it helps to completely change perspectives. I am trying to find a new way to describe why and how capitalism itself anticipates communism without producing a predictable 20th century Marxism argument.

CAVEAT: Of course, this just might fall completely flat, but thems are the breaks. So you can be skeptical of the result, since I am just attempting a thought exercise.

Change the World Without Taking Power: A decade later John Holloway’s challenge still unmet (Final)

Part 4: History as a continuous process

One of the real difficulties Holloway’s thesis on the crisis of capitalism poses to a critical analysis is that his very incisive critique of the failings of post-war Marxism is buried under his own terribly flawed grasp of labor theory. For instance, Holloway rightly criticizes the dominant Marxist view of capitalist crises as a potential trigger for a political revolution:

The orthodox understanding of crisis is to see crisis as an expression of the objective contradictions of capitalism: we are not alone because the objective contradictions are on our side, because the forces of production are on our side, because history is on our side. In this view, our struggle finds its support in the objective development of the contradictions of the capitalist economy. A crisis precipitated by these contradictions opens a door of opportunity for struggle, an opportunity to turn economic crisis into social crisis and a basis for the revolutionary seizure of power. The problem with this approach is that it tends to deify the economy (or history or the forces of production), to create a force outside human agency that will be our saviour. Moreover, this idea of the crisis as the expression of the objective contradictions of capitalism is the complement of a conception that sees revolution as the seizure of power instead of seeing in both crisis and revolution a disintegration of the relations of power.

The core of Holloways argument here is correct: post-war Marxists still expect the capitalist crisis to trigger a seizure of state power by the working class. This seizure of state power will then lay the basis for the construction of a communist society by the working class — a wholly fantastic delusion, with little realistic basis whatsoever in labor theory. However, Holloway then replaces this silly erroneous view with his own even more silly erroneous take on labor theory and crises:

The other way of understanding the ‘we are not alone’ is to see crisis as the expression of the strength of our opposition to capital. There are no ‘objective contradictions’: we and we alone are the contradiction of capitalism. History is not the history of the development of the laws of capitalist development but the history of class struggle (that is, the struggle to classify and against being classified). There are no gods of any sort, neither money nor capital, nor forces of production, nor history: we are the only creators, we are the only possible saviours, we are the only guilty ones. Crisis, then, is not to be understood as an opportunity presented to us by the objective development of the contradictions of capitalism but as the expression of our own strength, and this makes it possible to conceive of revolution not as the seizure of power but as the development of the anti-power which already exists as the substance of crisis.

To overcome the post-war Marxist model of capitalism as an objective, autonomist process that continues (only interrupted by the occasional crisis) until it is superseded by an outside force (the proletarian revolution) Holloway argues not that capitalism’s demise is premised on the process of accumulation itself (rather than a political revolution) but that there is no objective process! In contrast to post-war Marxism, Holloway denies there is an objective process underway in the capitalist mode of production, and he doubles down on this stupidity by agreeing with post-war Marxism that there are no forces at work within capitalism that must lead inevitably to its collapse.

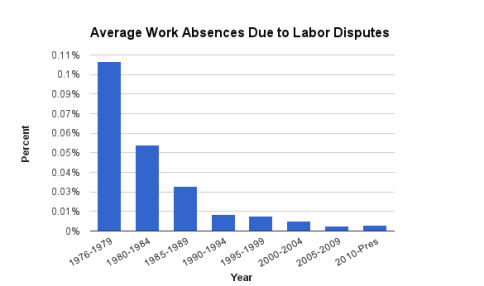

In place of post-war Marxism’s assumption that the political revolution will be triggered by a capitalist crisis, Holloway imports the class struggle into capital and proposes, “we and we alone are the contradiction of capitalism”, “we are the crisis of capitalism”. The glaring defect of Holloway’s attempt to resolve the theoretical impasse of post-war Marxism model of social revolution can best be demonstrated by a single chart (below).

The chart is from ThinkProgress, and the writer, Pat Garofalo, states:

“According to an analysis of Current Population Survey data by Matt Bruenig, the number of workers exercising their right to strike has plummeted since the 1970s:

Forty years ago, ‘an average of 289 major work stoppages involving 1,000 or more workers occurred annually in the United States. By the 1990s, that had fallen to about 35 per year. And in 2009, there were no more than five.’ Declining unionization certainly plays a role in this drop, but as Chris Rhomberg, associate professor of sociology at Fordham University, wrote, so too does labor law that gives employers all the advantages. ‘We have essentially gone back to a pre-New Deal era of workplace governance,’ he wrote.”

If the statement, “we are the crisis of capitalism” is taken to mean the workers’ class struggle produces capitalist crises, there is in fact no crisis at all according to the data supplied by the census department. Holloway needs to explain where he finds the “irruption of the insubordination of labour into the very definition of subordination” in this data. Frankly, when Matt Bruenig actually took the time to leave his progressive friends on Fantasy Island and do the research all he found was the very real and material subordination of the working class to the rule of the bourgeoisie — a class no longer even capable of fighting for its direct economic interests.

The so-called Great Moderation of the 1980s and 1990s was not just, nor even primarily, period of moderating inflation, but a cessation of the class struggle altogether. The collapse of the class struggle experienced over the last three decades, as shown empirically by Bruenig’s data, suggests that insofar as the demise of capitalism results from a subjective cause, it is not likely to happen. When Holloway argues against the classical view of capital as an objective process, he is actually arguing against the idea that the material requirements of the working class (the law of value) are an objective reality that must impose itself on the operation of the capitalist mode of production despite what takes place in the streets. He is arguing these material requirements can only make themselves felt through the class conscious (political) activity of the class. Without this political activity, therefore, a crisis of capitalism cannot be expressed. It becomes inexplicable then why the period of lowest rate of labor discontent is also the period of an incredible financial catastrophe and the collapse of fascist state management of capitalism.

Although the working class has followed the orders of capital to “‘Kneel, kneel, kneel!'”, the result is the collapse of the financial system along with the fascist state economic policy mechanism. The empirical data suggest the crisis that erupted in 2007-2008 resulted from an objective process that is in no way dependent on the political struggle of the working class — i.e., in no way dependent on the class struggle between wage labor and capital.

Wage laborers and labor

As I stated in the previous part of this series, what makes Holloway’s argument worth the time it takes to extract it from his flawed and wholly indefensible presentation of labor theory is that he does not simply import the class struggle into the definition of capital, and redefine the law of value as the “irruption of the insubordination of labour into the very definition of subordination” — both of which ideas are preposterous — Holloway inverts the class struggle so that it is now redefined not as a struggle of wage labor against capital, but as the struggle of wage labor against labor itself.

This inversion might seem like a theoretical ploy to overcome the impasse post-war Marxism encounters because it assumes capitalism will just endlessly loop through crisis after crisis until it is put out of its misery by a proletarian revolution — and to a large extent it is just this. But the real usefulness of Holloway’s theoretical gymnastics is that he can then re-conceive the social revolution in an entirely new way — as an anti-class struggle, a struggle that is both anti-political and anti-economic.

To say this another way, let’s suppose all the material requirements of communism already exist within the existing world market, what would we expect to see? As capitalism drew closer to its ultimate demise, and the working class approached its “final constitution” (Marx’s words to Bakunin), all the fetish forms of bourgeois society — politics, classes, democracy, the nation state, money, commodity, and capital itself — would appear to the working class precisely as that: meaningless fetishes lacking any substance whatsoever — as misery of a growing mass of unemployed workers, rampant speculation produced by a growing mass of superfluous capital, cronyism, empty political promises, accumulating debt, money that depreciates in your wallet, wages whose purchasing power declines from one day to the next and, most of all, labor that produces nothing of any value whatsoever. This would be expressed in a conscious antipathy not just toward this or that facet of present society, but a revulsion with social relations generally, and with the political relation founded on these social relations — a scream.

Holloway is, in effect, not describing an increasingly class conscious working class, but a mass of individuals bearing an emergent directly communist consciousness: a consciousness described in the German Ideology as requiring certain definite material preconditions and which emanates, not from bourgeois relations of production, but directly from the working class itself:

“In the development of productive forces there comes a stage when productive forces and means of intercourse are brought into being, which, under the existing relationships, only cause mischief, and are no longer productive but destructive forces (machinery and money); and connected with this a class is called forth, which has to bear all the burdens of society without enjoying its advantages, which, ousted from society, is forced into the most decided antagonism to all other classes; a class which forms the majority of all members of society, and from which emanates the consciousness of the necessity of a fundamental revolution, the communist consciousness, which may, of course, arise among the other classes too through the contemplation of the situation of this class.”

Proletarians and Communist consciousness

By inverting the class struggle and showing that this struggle must become a struggle not against capital, but against labor itself, Holloway maintains the working class cannot fight as a class, it can only fight against being a class. Essential to understanding why this is true we have to understand that every time the working class tries to fight as a class politically or economically, it is going to get its ass kicked as a class — it is going to lose. Over time, the response to this constant ass-kicking at the hands of the bourgeois class, naturally enough, is that the class stops fighting as a class, because it has more sense than fucking Marxists. Why would you continue to beat your head bloody against the same fucking wall time and again when you know you are going to lose?

By arguing the class struggle is the core of capital, Holloway does not throw light on capital as the penetration of insubordination into subordination as he believes; rather he shows why the absolute subordination of the working class must penetrate class (political) relations generally. This conclusion is certainly chilling, but simultaneously relieves us of the notions associated with post-war Marxism that some coming economic crisis will trigger a political revolution of the working class — a political confrontation between the classes that leads to socialism. Once we grasp this fact, the data of the last four decades makes sense; we now need not follow the failed post-war Marxist formula that Holloway so effectively critiques.

In addition to decades of empirical evidence the post-war Marxist formula does not work, we now have a theoretical proof derived not just from an argument against it, but an argument that also tries to introduce class struggle into the very definition of capitalist relations. Holloway carries the post-war Marxist argument to its extreme, most absurd, limits by trying to locate the class conflict at the core of capital. But the class struggle is, first and foremost, a political struggle, a struggle between wage labor and capital, bourgeois and proletarians. Holloway suggests there is no distinction to be made between political and economic relations: therefore, the class struggle must rest on the absolute subordination of the proletarians and it must reflect this subordination.

But this is only the beginning: Holloway’s argument also suggests there is no distinction to be made between capital and labor, reform and revolution, the old society and the new one, the revolution and everyday life, leaders and the masses, what exists and what is denied. To overcome these separations, Holloway argues, “actions must point-beyond in some way, assert alternative ways of doing:”

“The problem of struggle is to move on to a different dimension from capital, not to engage with capital on capital’s own terms, but to move forward in modes in [which] capital cannot even exist: to break identity, break the homogenisation of time. “

Holloway says this means the entire concept of revolution has to be rethought.

Reconceiving social emancipation

In chapter 11 — the final chapter of his book — Holloway must show how we get from a social process where the outcome is not determined by an objective process, to one that intensifies the disintegration of capitalism. Holloway thinks he has already pointed to a solution by redefining the social process “as being itself class struggle”. The crisis is the point at which “the mutual repulsion of capital and anti-labour (humanity) obliges capital to restructure its command or lose control.” The resolution of the crisis can either come through a restructuring of capital’s subordination of labor or a struggle to intensify the crisis.

On one side of this conflict is capital, trying to emancipate itself from labor, to literally make money from money itself through a growing mass of fictitious capital and insane speculative activity. On the other side is labor (or “anti-labor”, or “humanity” — or “what-the-fuck-ever”) whose drive is the refusal of dominance, the scream. Capital has to subordinate the working class once again to the production of surplus value, and this in turn depends on the fact the workers are propertyless. The enclosures of primitive accumulation is extended in entirely new areas (intellectual property), and in new regions (globalization)

Holloway argues the flight of labor (or “anti-labor”, or “humanity”, or “what-the-fuck-ever”) is hopeless until it becomes more than flight from capital, it must become “a reaffirmation of doing, an emancipation of power-to.” Okay, so how do we reaffirm our doing? One would think after ten chapters of criticism of Marxism Holloway would have some new ideas. One would be wrong, however. In the end all Holloway can come up with is this:

“But the recuperation of power-to or the reaffirmation of doing is still limited by capital’s monopoly of the means of doing. The means of doing must be re-appropriated.”

In English, Holloway is stating the proletarians must seize the means of production — put an end to property — that they must bring the forces of production under their control. It seems like pretty standard Marxist boilerplate — and it is — until Holloway says we must rethink this concept as well, a rethinking he then begins in what at first appears to be random thread of mindless gibberish:

“The problem is not that the means of production are the property of capitalists; or rather, to say that the means of production are the property of the capitalists is merely a euphemism which conceals the fact that capital actively breaks our doing every day, takes our done from us, breaks the social flow of doing which is the pre-condition of our doing. Our struggle, then, is not the struggle to make ours the property of the means of production, but to dissolve both property and means of production: to recover or, better, create the conscious and confident sociality of the flow of doing. Capital rules by fetishising, by alienating the done from the doing and the doer and saying ‘this done is a thing and it is mine’. Expropriating the expropriator cannot then be seen as a re-seizure of a thing, but rather as the dissolution of the thing-ness of the done, its (re)integration into the social flow of doing.”

The same is true of our conception of revolution itself: Holloway argues we must get rid of the idea that the social revolution is a means to an end:

“The orthodox Marxist tradition, most clearly the Leninist tradition, conceives of revolution instrumentally, as a means to an end. … Instrumentalism means engaging with capital on capital’s own terms, accepting that our own world can come into being only after the revolution. But capital’s terms are not simply a given, they are an active process of separating. It is absurd, for example, to think that the struggle against the separating of doing can lie through the state, since the very existence of the state as a form of social relations is an active separating of doing. To struggle through the state is to become involved in the active process of defeating yourself.”

Finally, Holloway argues we must rethink what capitalism and communism are all about:

“Capital is the denial of the social flow of doing, communism is the social movement of doing against its own denial. Under capitalism, doing exists in the mode of being denied. Doing exists as things done, as established forms of social relations, as capital, money, state, the nightmarish perversions of past doing. Dead labour rules over living doing and perverts it into the grotesque form of living labour. This is an explosive contradiction in terms: living implies openness, creativity, while labour implies closure, pre-definition. Communism is the movement of this contradiction, the movement of living against labour. Communism is the movement of that which exists in the mode of being denied.”

Holloway reconsidered

It probably is not too much to say, Holloway has no real idea how these three statements hang together as a roadmap for what must come next. And this is because, despite his attempt to break with post-war Marxism, he remains entirely under the thrall of its assumption of a political revolution. Since he has already rejected the idea of capitalism as an objective process whose operation is determined by the law of value, and replaced this objective process with the class struggle, Holloway is at a loss to explain the significance of his insights — he ends the book at the same impasse that can be found in any orthodox post-war Marxist treatment:

“How then do we change the world without taking power? At the end of the book, as at the beginning, we do not know. The Leninists know, or used to know. We do not. Revolutionary change is more desperately urgent than ever, but we do not know any more what revolution means. Asked, we tend to cough and splutter and try to change the subject. In part, our not-knowing is the not-knowing of those who are historically lost: the knowing of the revolutionaries of the last century has been defeated. But it is more than that: our not-knowing is also the not knowing of those who understand that not-knowing is part of the revolutionary process. We have lost all certainty, but the openness of uncertainty is central to revolution. ‘Asking we walk’, say the zapatistas. We ask not only because we do not know the way (we do not), but also because asking the way is part of the revolutionary process itself.”

If the revolution is not the means to an end, it must be the end itself, a permanent feature of society. This leads us back to Holloways concept of communism as “the movement of that which exists in the mode of being denied.” This is an interesting idea, since it suggests communism is already present within existing society as labor theory indicates. Communism, therefore, is not something constructed “after the revolution”, but the actual mode of present society that is denied by capital.

The instrumentalism of post-war Marxism fails precisely because it does not recognize the existence of an already existing communism within present society. This essential blindness of post-war Marxism can be seen when Andrew Kliman stupidly criticized David Graeber for suggesting Occupy act as if the future society already existed. I wrote at the time: “Professor Kliman prefers to “foreshadow” the non-existent, and derides Graeber for asserting the thing foreshadowed in action already exists in embryo.” As a dyed-in-the-wool anarchist, Graeber was actually the real Marxist in the debate, since he acted as if (in Marx’s and Engels’ own words) the premises of communism are already in existence.

If, following Holloway, we act as if communism is already the present mode of society whose existence is being denied by capitalist relations, labor must be the active forms of this denial. Labor itself is activity that denies the existence of an already existing communism. This suggests our focus must be on labor itself, not the state, on putting an end to the active denial of communism. All of this shit is already present in Holloway’s argument. Why it never emerges in his book is completely fucking beyond me.

I think the core of Holloway’s critical argument then can be boiled down to three points:

- “To think in terms of property is, however, still to pose the problem in fetishised terms”;

- “Expropriating the expropriator cannot then be seen as a re-seizure of a thing, but rather as the dissolution of the thing-ness of the done, its (re)integration into the social flow of doing”; and,

- “What is important is the knitting or re-knitting or patch-working of the sociality of doing and the creation of social forms of articulating that doing.”

It is obvious the sociality of doing can only be established by the abolition of wage labor. Wage labor is precisely what alienates the directly social activity of the producers from them and establishes this social activity as a thing independent of them. And putting an end to wage labor puts and end both to the “thingness” of productive activity (commodity production) and the fetish of property (labor power). Everything, in other words, points toward the abolition of wage labor itself, to the end of the working class as a class. By making consumption dependent on wage labor, the actual abundance already present in society appears as scarcity. This scarcity is wholly an artifact of the limited quantity of dollars in your wallet; it is not real.

This is demonstrated by the growing unemployment, an ever increasing mass of speculative capital, and, above all, an ever increasing mass of debt being accumulated in every country at present. Debt cannot buy what doesn’t exist — it presupposes massive quantity of material abundance. In short the formula implied by debt is this: massive debt = massive abundance. The dependence of so-called “economic growth” on the constant accumulation of debt, in other words, implies that all the conditions for communism already exist, save one: abolition of wage labor.

The material conditions for a direct supercession of capitalism by communism already exists empirically in the form of growing unemployment, rampant speculative capital and an ever accumulating pile of public and private debt. The question for us is this: will this communism be imposed on society in a final and complete collapse capitalist relation, bringing capitalist production to a standstill and triggering a catastrophe. Or, will it be realized through the determined fight to progressively reduce hours of labor?

We don’t really have any other choices.

My May Day Post: The Marxist Academy and the Myth of “Working Class Consciousness”

This May Day, as in all previous May Days going back almost to its establishment, will be marked by the indifference of the working class, at least in the United States, to its arrival. The odd thing about this is that May Day was born here in the United States as an expression of working class power and its determined struggle for the reduction in hours of labor. Yet here, more than in any other country, it passes almost unnoticed by the very class that created it through its own independent power. That it should be met with indifference here in the country of its birth is a paradox that requires explaining — if for no other reason than it points to a fundamentally troubling aspect of communist theory in its orthodox Marxist and anarchist variants: the apparent failure of the working class to rise to its historical mission as gravedigger of capitalism, to acquire what is commonly referred to as a class consciousness.

Part of this paradox can be explained by visiting a paper recently published by Alberto Toscano on the problem posed by Post-Workerism interpretations of Marx’s and Engels’ argument in which a worker, Nanni Balestrini, complains:

Once I went to May Day. I never got workers’ festivities. The day of work, are you kidding? The day of workers celebrating themselves. I never got it into my head what workers’ day or the day of work meant. I never got it into my head why work should be celebrated. But when I wasn’t working I didn’t know what the fuck to do. Because I was a worker, that is someone who spent most of their day in the factory. And in the time left over I could only rest for the next day. But that May Day on a whim I went to listen to some guy’s speech because I didn’t know him.

As I stated in a recent interview:

What I find interesting about this quote is that, obviously, May Day does not “celebrate work”, but celebrates a victory in the working class’s struggle for a reduction of hours of labor. What began as a celebration of a victory marking a step toward the abolition of labor became, over time, redefined as the celebration of the thing to be abolished, labor. But what is equally interesting about the quote is that the worker quoted, while apparently ignorant of this history, recognizes the idiocy of celebrating wage slavery. Even without realizing it, the worker reestablishes the original significance of the day.

This is an observation that seems lost on the critics of the Occupy and Tea Party movements.

What do I mean by “Private Property”?

Neverfox asked me:

Neverfox asked me:

“What do you mean, exactly, when you say “private property”?”

Let me begin by avoiding the obvious (but wrong) answer to this question. While many strands of communism define property as a relation between the individual and things, historical materialism, defines property as a relation between individuals. What do I mean by this?

Usually, when Marxists are asked this are asked this, they respond by identifying objects that meet the criteria of political-economy as property. Then they subtract from this, specific objects that would not fit the definition of private property for their purpose as “the objects to be seized”. They will say, for instance, an automobile is personal, not private, property under their definition, but an automobile factory is private property. When pressed on this — e.g., “but what about taxis?” — they will again divide the objects between things for personal use and things for use as capital.

Somehow, after all of this they arrive at an approximation: “things which are collectively required versus things that are not.” They then propose that things collectively required are “private property” while things that are not collectively required are not.

The problem with this view is that among the “things collectively required” by us, is us — we need each other. And, we need us, not just in the religious or ideal sense of that term, but in the very physical sense. As a species we would die out without mating; and our civilization would die out without our common pool of labor power.

Now, think about that: What is the easiest solution to this problem: make everything into the common property of society. The collectively required means become the property of the whole community — now extend this idea to sex and labor. You immediately run into the problem: women become the collective property of men. And, individual labor becomes the collective property of the commune.

This implies that this entire approach to the idea of private property is a dead end, that it contains a fallacy in itself.

So, Marx, in his work, Private Property and Communism, tried a completely different approach to the question, which did not lead to this absurd outcome. As opposed to the Utopians, he proposes communism as not the seizure of property, but its transcendence. In other words — to the best of my understanding — to overcoming the insatiable impulse to have stuff.

What he calls “primitive communism” seeks only to grasp private property and make it the common property of society, and, even if successful, only succeeds in sharing poverty out. Society is turned into a poverty stricken workhouse — he rejects this communism. In this primitive communism “want is merely made general, and with destitution the struggle for necessities and all the old filthy business would necessarily be reproduced” — this is from the German Ideology. Moreover, he argued, this primitive communism could not survive long in the competitive environment of the world market:

Without this, (1) communism could only exist as a local event; (2) the forces of intercourse themselves could not have developed as universal, hence intolerable powers: they would have remained home-bred conditions surrounded by superstition; and (3) each extension of intercourse would abolish local communism.

Yesterday, I came across a post that follows a similar line of argument:

In fact, as Berman points out, Marx envisioned two very different kinds of communism. One, which he wanted and approved of, was a “genuine resolution of the conflict between man and nature, and between man and man”; the other, which he dreaded, “has not only failed to go beyond private property, it hasn’t yet attained to it”. What this means is that, for Marx, genuine communism was only possible on the basis of the legacy of a mature and fully developed capitalism. The communism we have seen in the 20th century, and which most people rightly dread and condemn, is more a kind of state-capitalism, brutally managing poverty and imposing industrial development. The years since Marx’s death have seen very many examples of the second kind of communism; but none yet, unfortunately, of the first.

Compare this passage and Marx’s above passage to the fate of the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China.

Primitive communism understands itself only in relation to private ownership and the inequality of capitalist society. This was the basis of his differences with the anarchists. He argued that if Capital had not completed its historical mission of developing the productive forces sufficiently to abolish want. The commune would still suffer from poverty and would have to complete it on its own. This would require some definite means of apportioning the requirement for labor among the members. This means of dividing up the necessary labor would constitute the remnants of the bourgeois state. Whether people wanted it or not, their consumption would be tied to their labor until the need for labor disappeared. Compulsion would continue to exist in the form that access to the means of consumption would necessarily be measured by the labor contribution of each member.

The anarchists rejected this, but he wasn’t persuaded — this, unfortunately, led in part to the first big split in the workers’ movement. But, even after the split this very same difference reemerges in almost complete form within the Marxist trend itself.

The true resolution, Marx argued, is the abolition of want, of poverty, and of necessary labor. It is, in essence, the abolition of the need to have things since, under these conditions the need to physically possess anything dies out — any material thing one might want is readily present in abundance. With this material abundance, he argues, the impulsive need to possess nature and other individuals must die out as well.

So, in a broader sense of the term, as he defines it, private property is the inverse expression of general scarcity. It is not a “thing to be seized”, but a relationship with nature and other individuals to be abolished.

Finally, Marx insisted:

Communism is the necessary form and the dynamic principle of the immediate future, but communism as such is not the goal of human development, the form of human society.

I hope that helps answer this. The essay on private property and communism is quite better argued than I just did.

Bakunin’s Anarchism, Marxists Dogmas and Marx

I set out to write a piece on Murray Rothbard and communism. Instead, I got bogged down by this detour into Marx’s theoretical differences with Anarchism. The day progressed, Marx and Bakunin would not stop their bickering and let me leave.

Alas, Murray will have to wait for another day.

***

There is an interesting response given by Karl Marx to a denunciation of his views by Mikhail Bakunin in notes on quotations Marx pulled from Bakunin’s book, Statism and Anarchy.

Bakunin writes:

They say that their only concern and aim is to educate and uplift the people (saloon-bar politicians!) both economically and politically, to such a level that all government will be quite useless and the state will lose all political character, i.e. character of domination, and will change by itself into a free organization of economic interests and communes. An obvious contradiction. If their state will really be popular, why not destroy it, and if its destruction is necessary for the real liberation of the people, why do they venture to call it popular?

Marx replies to this:

Aside from the harping of Liebknecht’s Volksstaat, which is nonsense, counter to the Communist Manifesto etc., it only means that, as the proletariat still acts, during the period of struggle for the overthrow of the old society, on the basis of that old society, and hence also still moves within political forms which more or less belong to it, it has not yet, during this period of struggle, attained its final constitution, and employs means for its liberation which after this liberation fall aside. Mr Bakunin concludes from this that it is better to do nothing at all… just wait for the day of general liquidation — the last judgement.

The answer Marx gives to Bakunin is extremely telling not simply in relation to Anarchist ideology, but — more important for our times — in relation to the present day Marxists.

In Bakunin’s understanding Marx was making the argument that some definite period of time after the overthrow of the political rule of the capitalist class, the working class would not immediately abolish its own coercive political rule, but would embark on some period of a transitional ‘worker’s state’ (a term Marx accepted in another context, but did not endorse). In Marx’s model, says Bakunin, during this period the worker’s state would “uplift the people … both economically and politically…” to some certain level of social development where the worker’s state, and its coercive functions, would become obsolete.

Bakunin proposes that a contradiction lay at the heart of Marx’s position: If the worker’s state is truly popular — that is, if it truly enforces certain rules that are commonly and overwhelmingly supported — why can’t this coercive power be done away with entirely? And, if its coercive power must be done away with for the society to enjoy real unfettered association, why is Marx calling it a popular power?

Marx corrects Bakunin to clarify that his position is expressed in the Communist Manifesto and not in the words Bakunin employs to describe them. He then continues to explain the basis of the ideas in the Manifesto: First, upon coming to power the Proletariat takes political control of society under definite economic conditions, and not on the basis of some idealist notions independent of those economic conditions. Since, in Marx’s theory, the State arises from the material conditions of society and does not exist independent of those conditions, it is not possible for coercion to just disappear until the conditions giving rise to it disappears as well. Try as society may like to abolish the functions of state power on the morning of the new order, still the actual economic conditions on which this new order rests have their reciprocal influence on society. Bakunin’s argument that in no case should the Proletariat establish its political rule amounted to a demand that it not take power until it could immediately abolish itself, its condition of existence up until that time, and all other classes in society, i.e, until Capital having completed its historic role of developing the productive forces of society and run its course, collapsed on its own.

Second, Marx’s meaning in this context is not always properly understood — and, this is where Marxists get themselves into hot water. State power is always coercive — it is the imposition on the individual of conditions of her own activity against which the individual naturally rebels. The coercive functions of the ‘worker’s state’ are no different in this regard to the coercive functions of any previously existing state. It may be uncomfortable for us to assert this fact, but it in no way can be ignored — for the individual the coercion of a ‘worker’s state’ is, in its effect, no different than the coercion of the capitalist state. With regards to the individual this rule is despotic, and the fact that, in this case, the despotic hand is encased in a democratic glove does not change its despotic nature in the least.

However, the discussion of this despotic rule is wrongly limited to the actual machinery of state, as if the coercion of capitalist society consisted entirely of an armed body of men and women enforcing the naked rule of the capitalist class. In fact, coercion here has to be seen in a broader context: it is also coercion that the worker, deprived of all means of production, must sell herself into slavery in exchange for wages. It is also coercion that no one may access the means of consumption in society except on the basis of exchange of equal values — of money exchange. It is also coercion that the worker cannot sell her labor for wages except on condition that she work a period of time in excess of the value of these wages for the exclusive benefit of the capitalist. Each of these examples is a form of coercion prevalent in capitalist society. And, each is understood by all members of society to be the conditions under which the whole of capitalist economic activity is carried on. So pervasive are they, that these forms of coercion appear to us not a forms of coercion at all but a basic and eternal condition of human existence. Moreover, in many cases these forms of coercion appear altogether accidental — for instance, it is possible to strike it rich in the lottery, write a best seller, or start a successful rock band and be able to avoid having to spend your days in a cubicle sending or answering email or working the checkout counter at WalMart.

The communist movement of society has the aim not simply of abolishing the machinery of state — the body of men and women who arrest you if you violate the law of equal exchange of value by pilfering in WalMart, the judge who presides over your trial, the district attorney who prosecutes you, the jailor to whose care you are remanded after conviction, and the politicians who passed the law into being — it also has the task of ending exchange of values and all other forms of economic coercion as the basis for the individual’s activity.

In the conditions under which Marx carried on his debate with the ideas of the Anarchist Bakunin, it is clear that society had in no way been prepared for the immediate abolition of the State in its entirety. Capital had not by any means so transformed the social economic landscape that Marx could imagine it prepared for not only the abolition of the political rule of the capitalist class, but all class rule and classes themselves. The economic development of society had definitely not reached the stage that the Proletariat could abolish itself as a class.

And, why is this? In my opinion, every scenario Marx could see of a possible assumption of power by the Proletariat, society was still in the grip of scarcity. Although, as he acknowledged, Capital had performed a prodigious feat of transforming the conditions under which labor was undertaken by society, society had not yet made the abolition of necessary labor possible. Taking power under those conditions would, of necessity, involved realizing a communism of relative poverty — the sharing of the conditions of scarcity under a more or less ‘equal’ apportioning.

And, what did Marx think was the rule under which this scarcity would be shared out? “From each according to his labor, to each according to his work.” Access to the common fund of consumption had to be on the basis of the labor of each member of society. Each would receive from this common fund no more than she contributed to this fund. Even if we assume the immediate abolition of the entire machinery of the old State and its replacement by the association of society — and Marx made precisely this assumption — nevertheless society would be imposing on the former capitalist and State officials the same coercive conditions of activity that nature imposed on it:

“Do you want to eat? Get a job! If you won’t work because you are too dainty and work is beneath you, then you will starve!”

Thus, society would take a step forward in its historical development in that, for the first time, labor would be required of all members of society. But, this step was not the final one to be taken: the final step consisted of the abolition of this very requirement imposed equally on all members of society to engage in labor. The replacement of the rule: “From each according to his labor, to each according to his work”, by a new rule, “”From each according to his labor, to each according to his need”, required not simply the assumption of power by the Proletariat, but a certain definite material condition — the emergence of a society of abundance.

He did not hesitate to make his opinion known to the Anarchists on this issue, and he did not hesitate to make it known to his so-called followers as well, when, as happened in the Gotha Program, they came up with all sorts of silly ideas. Marx’s response the Gotha was pretty blunt: Upon taking power the Proletariat would break the monopoly of the capitalist class over the means of production. Workers would not receive the entire proceeds of their labor, but only a portion; the rest of which would go to cover replacement of the common means of production, expansion of those means, and insurance against losses. From the remaining fund would be deducted general social costs of administration, means for common satisfaction of needs like medical care and education, and means for those who are not able to work. What portion of the common labor would be needed for these items could only be decided democratically by the whole commons — and, in all probability those who lost the vote would feel coerced by the majority, since these costs would still be deducted from them despite their disagreement. What was left after this had been accomplished would then be divided according to their contribution.

Marx continues:

What we have to deal with here is a communist society, not as it has developed on its own foundations, but, on the contrary, just as it emerges from capitalist society; which is thus in every respect, economically, morally, and intellectually, still stamped with the birthmarks of the old society from whose womb it emerges. Accordingly, the individual producer receives back from society — after the deductions have been made — exactly what he gives to it. What he has given to it is his individual quantum of labor. For example, the social working day consists of the sum of the individual hours of work; the individual labor time of the individual producer is the part of the social working day contributed by him, his share in it. He receives a certificate from society that he has furnished such-and-such an amount of labor (after deducting his labor for the common funds); and with this certificate, he draws from the social stock of means of consumption as much as the same amount of labor cost. The same amount of labor which he has given to society in one form, he receives back in another.

Here, obviously, the same principle prevails as that which regulates the exchange of commodities, as far as this is exchange of equal values. Content and form are changed, because under the altered circumstances no one can give anything except his labor, and because, on the other hand, nothing can pass to the ownership of individuals, except individual means of consumption. But as far as the distribution of the latter among the individual producers is concerned, the same principle prevails as in the exchange of commodity equivalents: a given amount of labor in one form is exchanged for an equal amount of labor in another form.

At this point, however, Marx is not finished: he goes on to explain why even this seeming logical and just division of the product of labor among the members of society actually conceals an unequal distribution, because although the return for work is the same, people are not. Although this inequality in fact is abhorrent — an indifference to the particular circumstance of each individual — there is, in his mind, no other basis that such division can be made. Thus, for Marx, the end aim of the transition is not an equal return on the labor contribution of each, but ending all connection between the labor each member of society contributes and the means they can access. The rule that everyone must work is itself abolished — or withers away.

And, this is where Marxists get into hot water — they impose on Marx’s comments the completely unhistorical dogma that the communist movement of society is necessarily split between the period beginning with the political overthrow of the capitalist State and the period during which the transitional form of Proletarian rule comes to an end. They are only parroting Marx in his argument with Bakunin, while understanding none of his argument.

At the beginning of this period of social transformation the political rule of the Proletariat is “stamped” with the conditions of the capitalist society that has just been overthrown. It follows from this that Marx is not making an unhistorical division between this point in time and the point where the Proletarian rule ends, but is precisely emphasizing that the actual conditions governing capitalist society, when this event takes place, must be studied and understood. It follows that his comment cannot be taken as a hard and fast rule, still less elevated into a dogma as the Marxists do, that there is some necessary period of transitional state between the overthrow of capitalist rule and a stateless, classless society. Capitalist society is by no means the same creature in 1874 that it is in 1917, 1929, or 2011. In each case the practical tasks imposed by the assumption of political power by the Proletariat must be different as the new society is being “stamped” with a decidedly different set of circumstances.

What are those conditions today? Are they the same as they were in 1874 or 1875? Are they even the same as they were in 1929 or 1970? Does Marx’s words have the same meaning in his day as they do now that Fascist State expansion — the continuous destruction of surplus value and its replacement by ex nihilo pecuniam — has become a condition for all economic activity?

Marxists have no answer to these questions because instead of making an analysis of present day conditions of capitalist society, they insist on taking Marx’s debate with Anarchists completely out of its historical context and worshiping dogmas.

Marx’s Theory or Marxist Theory?: How Daniel Morley (mis)Educated Anarchists

As Marx observed, no society has imagined itself into existence, which is to say, women and men do not set out to build their society according to some preconceived blueprint. The social relations resulting from human action appear to us in later times as the preconceived ideas of the creators of those social relations when, in fact, the ideas never existed until the social relations had already come into being.

An error arises in historical study: we attribute to the earlier periods of history ideas that existed nowhere during that earlier period, but only arise as a result of human action during that period. In the United States, for instance, every sort of nonsense, including wars of aggression and relentless Fascist State expansion, are promoted and justified by reference to the Ideals of the so-called “founding fathers” — ideals of Liberty, Equality, Right, etc. Society appears always in the grip of long dead men, whose ideas hover over us like ghosts, guiding us along some preconceived path of development. We, on the other hand, are merely the possessed, who, having been invaded by the ideas of the dead, only act out these ideas — see, for instance, Francis Fukuyama’s “The End of History”, where, following Hegel, Fukuyama imagines the whole of social development after 1806 as only the universalization of the ideals of the French Revolution, and, which ends with the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Marx offered a counter-argument to the notion that history is the unfolding of the Idea in human society: these ideas themselves emerge out of the material social relations and circumstances of women and men.

History is nothing but the succession of the separate generations, each of which exploits the materials, the capital funds, the productive forces handed down to it by all preceding generations, and thus, on the one hand, continues the traditional activity in completely changed circumstances and, on the other, modifies the old circumstances with a completely changed activity. This can be speculatively distorted so that later history is made the goal of earlier history, e.g. the goal ascribed to the discovery of America is to further the eruption of the French Revolution. Thereby history receives its own special aims … while what is designated with the words “destiny,” “goal,” “germ,” or “idea” of earlier history is nothing more than an abstraction formed from later history, from the active influence which earlier history exercises on later history.

Not according to the Marxist Daniel Morley, however. In contrast to Marx himself, Daniel argues that the communist movement of society consists entirely of the development of ideas: the communist movement of billions of people is already prefigured in the ideas of Karl Marx — society are only acting out these ideas; incompletely for the most part, with a great deal of hesitation, and, on occasion, by going back over the same ground twice. Thus, the refusal of Anarchists to acknowledge the role of theory — and, in first place, Marxist theory — is the source of much dissatisfaction on Daniel’s part.

…there is a strong tendency in Anarchism to reject theory as a scientific study of society, as they associate this with the intellectual elite and inaction. For this reason they tend to see all talk of ‘historical laws’ in society, and of the objective roles of various classes, as intellectual charlatanism, as an idealist … invention with which to confuse the masses into accepting our leadership…

Because of their rejection of theory, many Anarchists have resorted to simply describing the problems of capitalist society, and proposing antidotes as superficial as the act of simply inverting the names they give to capitalist oppression…

Rather than study the causes for all these social problems, the Anarchists would treat them as arbitrary, and all that is needed to overcome them is for society to somehow collectively realise that it is suffering under some arbitrary injustice, and then collectively liberate itself. Political ideas, if they are complex … are complex because society itself is extremely complex, has a long history, and demands that serious attention be paid to it if it is to be changed in accordance with our wishes.

Morley’s argument here is simple: society is so complex that without theory a stateless and classless society will not emerge. He chides the Anarchist movement for its refusal to understand this important fact.

The problem with this sort of thinking, of course, is that it is Marx himself who exposes this idealist conception of human history for what it is: a sham, an inversion of the real movement of society, and, hence, to be explicitly rejected. If Marx is to be understood by Marxists, they will have to address this logical loop introduced by Marx himself into his work: if his theory and methods are indeed scientific, they are unlikely to have any significant impact on the revolutionary transformation of society. Communist theory is not only unimportant to the process of social development as a result of its faint influence on events, according to Marx it must be unimportant to this process.

Both the strength and the weakness of theory is that it brings us to conclusions that are counterintuitive — that are not empirically derived. Precisely when communist theory could make the greatest possible contribution to the communist movement of society theory will probably have its least impact. For example, the movement of the unemployed in this crisis aims at precisely the goal theory states it should not. While the unemployed are demanding increased Fascist State spending to create jobs or provide a subsistence income to the unemployed, theory argues for a general reduction of both Fascist State expenditures and hours of labor. Communist theory is inconsequential to the process precisely because no one but Marxists, Anarchists and Libertarians, is consciously trying to create a communist society. Society at large are mainly responding to their immediate empirical circumstances. If these empirical circumstances did not, of themselves, lead to a communist movement of society, there is nothing communists could do to impose it on society.

In Daniel’s view the problem created by the counterintuitive nature of revolutionary social theory can be circumvented by a committed cadre of women and men who have both achieved some degree of familiarity with the theories of thinkers like Marx, Rothbard or Kropotkin, and who have won positions of political leadership among the larger mass of the working class. Indeed, Daniel argues the requirement for such a leading group of committed theoretically adept activists is so obvious that Anarchists, despite their explicit rejection of this “vanguard party” model, nevertheless also embrace it in one guise or another:

Contrary to Anarchist hopes, political leadership in our society is necessary for the working class. It could only be discarded, made superfluous, if the working class had the time and inclination to collectively develop revolutionary theory, collectively grasp the need for a revolution, and therefore organise it at once. The very existence of famous theorists such as Marx and Bakunin, who do play a leading role (whether they like it or not) by developing theory with which to educate the movement, is proof that in capitalist society this is not the case. Some Anarchists propose that, instead of a leadership of people, we have a leadership of ideas. Actually, this shows how the objective necessity for political leadership forces its way into Anarchist theory all the time. Only they give it another name instead. Anarchist theorists, themselves acting as leaders by developing theory to influence society, have variously made use of concepts such as ‘helpers’ of the working class, working class ‘spokesmen’, revolutionary ‘pathfinders’, the need for a ‘conscious minority in the trade unions’, or Bakunin’s concept of a disciplined Blanquist ‘directorate’ for the revolution. They use these terms but do not explain why they are necessary and how they really differ from political leadership. Why does the working class need helpers, pathfinders, a directorate, spokesmen, or a conscious minority? And what role would such people play? And if we merely have a leadership of ideas, then what of the people who developed those ideas (for they weren’t developed by the whole working class in a collective, uniform way), who presumably can explain them best, who can be most trusted to put the ideas forward in trade union negotiations, which, after all, cannot involve the whole working class at once? To change the name of something is not to change its essence.

The problem with this is not, as Daniel alleges, that Anarchists actually do follow a model only superficially different from Marxists, it is that he attributes the general lack of revolutionary theoretical development among the working class as a whole to the lack of time in which to develop this theory. Daniel’s argument that working people “lack the time” to develop revolutionary theory also appears earlier in his essay to explain why working people cannot directly manage production:

It is class exploitation and long hours of work that mean that in our society, workers cannot plan and direct production themselves, firstly because the capitalist class produces for their own private profit, and so cannot permit workers a say in controlling that profit, and secondly because workers do not have the time to democratically plan society … Only a globalised economy, a global division of labour … harmoniously planned on a global scale … can liberate the working class and put ordinary people in control, since only the high productivity it creates, and the technological sophistication involved, can shorten the working week to allow for mass participation …

The argument comes off as strained in both cases: owing to long hours of labor the workers lack the time to develop revolutionary theory on their own, and they also lack the time to democratically plan and direct production. If they had the time, and if they had the inclination, and if the capitalist class did not direct production for the sake of profit, the working class would not need theorists like Marx, nor the management of production by capitalists and communist technocrats. Since historical development is only the unfolding of a preconceived revolutionary blueprint for a new society through the activity of working women and men; and, since, owing to the lack of time, inclination, and the profit motive, working women and men cannot develop the blueprint they must afterward unfold through their activity, the theories of Marx and Bakunin become vital, and, with this, a committed cadre who have mastered the blueprint and can direct the rest of the working class in its realization.

The problem with this Marxist model is that Marx himself was not the kind of arrogant imbecile who thought he could dictate the course of human history, so he never left a theoretical blueprint for a new society. He did not even operate in such a way during his lifetime to impose some necessary model of the unfolding class struggle on the class struggle. He decried sects and sectarianism within the working class movement, which he described as those who, “demanded that the class movement subordinate itself to a particular sect movement.” In 1868 he wrote of one such sectarian incident:

You yourself know the difference between a sect movement and a class movement from personal experience. The sect seeks its raison d’être and its point d’honneur not in what it has in common with the class movement, but in the particular shibboleth distinguishing it from that movement. Thus when, in Hamburg, you proposed convening a congress to found trades unions, you could only suppress the opposition of the sectarians by threatening to resign as president. You were also forced to assume a dual personality, to state that, in one case, you were acting as the leader of the sect and, in the other, as the representative of the class movement.

The dissolution of the General Association of German Workers provided you with an opportunity to take a big step forward and to declare, to prove s’il le fallait [if necessary], that a new stage of development had been reached and the sect movement was now ripe to merge into the class movement and end all ‘eanisms’. With regard to the true content of the sect, it would, like all former workers’ sects, carry this as an enriching element into the general movement. Yet instead you, in fact, demanded that the class movement subordinate itself to a particular sect movement. Your non-friends concluded from this that you wished to conserve your ‘own workers’ movement’ under all circumstances.

Compare Marx’s attitudes toward sectarianism within the working class movement to Daniel’s view of the role of Marxists and Anarchists cadre within the working class movement:

Syndicalist Anarchists propose that a general strike, involving the vast majority of the working class, can be sufficient to overthrow capitalism, and moreover has the advantage of doing so without a party leadership. But the history of general strikes teaches otherwise – both in that on their own they are insufficient to overthrow capitalism (for we have had many general strikes but still have capitalism) and in that trade unions do have political leadership in them. Unfortunately, this leadership rarely has a determined revolutionary mission and tends to sell out general strikes. So the demand for a general strike must also be accompanied by a political struggle against the ideas of the reformist trade union leadership. But history has shown that such a struggle does not emerge, and certainly does not succeed, in a purely automatic fashion. In a general strike some organised political grouping must raise the idea of the need to use the strike as a launch pad to overthrow capitalism so that the working class can build socialism. And such an organisation would therefore be playing a leading role. Its task must be to win the struggle, to defeat the reformists by convincing the mass of the working class that its ideas are correct and necessary, in other words its task is to lead the working class to take power and overthrow capitalism.

Such is Daniel’s elaboration of the Marxist model of the relation between revolutionary theory and the working class movement. In contrast to Marx’s own view that sects are poisonous to the working class movement and should merge themselves into the broader working class movement, Daniel argues Marxists and Anarchists should “win the struggle, to defeat the reformists by convincing the mass of the working class that its ideas are correct and necessary…”

And, if the overthrow of capitalism requires the leading role of a sect utilizing the theoretical insights of Marx, Proudhon, or some other writer, how much more necessary would this sect be to managing the post-revolutionary society as it attempts to actually build a stateless and classless society. Thus, after the overthrow of the capitalist state, the working class is subject to more or less the same limitations as prevent it from theoretically preconceiving the overthrow of capitalism — it lacks the time to learn how to manage a complex, sophisticated society, and cannot manage the new society directly until the development of the productive forces of society allows for a general reduction in hours of work:

But a workers’ state, and genuine revolutionary working class leadership, is not the end goal for Marxists; we too see the need for a stateless society. That can exist only when the objective conditions that require a state apparatus (class struggle) have disappeared. In other words, when the working class has dissolved itself as a class by dissolving all classes, by uniting humanity in a global plan of production that leaves no lasting material antagonisms between classes or nations, and when production has attained such a level that the working week is sufficiently shortened so that all may participate in education and running society, then coercion and subjugation will have no objective role, and become worthless.

The problem, of course, with this model of a necessary leading role of a committed cadre to realize a stateless and classless society is that it is a complete fantasy that appears nowhere in Marx’s writings!

Since, Marx affords no role to revolutionary theory in his model of a communist movement of society, he did not propose a necessary role for a theoretically developed vanguard to lead the working class either before or after this revolution had erupted, nor did he propose that the present state should be replaced by anything other than the management of society by an association of society. This so-called theory of Marx is nothing more than an invention out of whole cloth by an insignificant sect that purports to speak in his name, but has yet to understand a single word he actually set to paper.

In Marx’s theory the stateless and classless society emerges directly out of the ruins of capitalist society. It arises not out of some theoretical insight into the inherent laws of capitalist society, but out of the practical experience of the members of society. True to his rejection of the Idealist model of history, the actual development of society places its members in circumstances where the actual necessity of a classless and stateless society is grasped empirically by them and does not arrive as the received wisdom of a handful of sectarians. This event presupposes, as Marx argues in the German Ideology, the actual empirical existence of women and men in their World Historical circumstances, which again presupposes that profit has ceased to be the motive force of production precisely because the actual development of the productive capacity of society has already made such motive impossible to continue not just in one or a few countries, but throughout the World Market as a whole. This latter condition presupposes that production of wealth itself is no longer compatible with the capitalist mode of production — that it cannot continue in the form of capitalist wealth, and, if it is to continue at all, must take the form of immediately material wealth, of mere means subordinated to the needs of the members of society, rather than an alienated power standing over them.

Marx’s differences with the other leaders and theoreticians within the working class movement did not hinge on their acceptance of his model of historical development — which model plays absolutely no role in society’s actual development — but with their insistence on one or another blueprint for a new society as the mode of society’s necessary activity. In the German Ideology, he expresses this disagreement directly:

Communism is for us not a state of affairs which is to be established, an ideal to which reality [will] have to adjust itself. We call communism the real movement which abolishes the present state of things.

Until Marxists grasp the importance of this statement and shed their sectarian attitude toward other trends of communist thought, and toward the working class movement in general, it will not simply be in violation of Marx’s revolutionary spirit, but also in violation of his actual theory. In Marx’s theory, there is no basis for a sectarian division among the various threads of communist thought — Marxist, Anarchist or Libertarian — nor any basis for a sectarian division between these threads of communist thought and the working class movement.

It is up to Marxists to take the first step in the direction of ending the sectarian division within the working class by dissolving their trend and its innumerable petty organizations entirely.

Challenging The Paradigm: A reply to PunkJohnnyCash

In his thought provoking essay, Capitalism vs. Communism Challenging The Paradigm, I think PunkJohnnyCash has posed exactly the right question for our times:

Can the Capitalism vs. Communism paradigm be challenged just as so many of us have found the flaw in a left-right paradigm?

To my mind, this is the most important question of the year as it closes and we begin 2011.

What I have tried to argue in my posts, What help for the 99ers?, and on my blog for some time, is that the demand of the Left for the abolition of Capital and that of the Right for abolition of the State are the mirror forms of the same demand for the abolition of unnecessary Labor. Capital is a mode of production of surplus value based on the continuous extension of labor time beyond that duration necessary to satisfy human need. The State is nothing more than this same mass of superfluous labor time congealed into the form of a repressive, expansionist machinery of political, economic, legal and military coercion.

In economic terms, the State is the necessary companion of Capital, because it provides the types of superfluous expenditures which become increasingly important to Capital. As the mode of production achieves an extraordinary high level of development, the unprecedented productivity of labor itself becomes a barrier to profitable investment. The enormous and growing quantities of goods issuing from industry rests on the productive activity of an ever shrinking number of productively employed laborers. At the same time, an ever increasing mass of laborers are utterly cut off from any productive employment, and would be cut off from all employment were it not for the direct and indirect expenditures of the State.

At the same time, in Capital, the State — long a vile, unspeakably filthy, grotesque pustule on the body of human society — found a new source of superfluous economic nourishment on which it could feed; enlarging itself, establishing new tentacles deep into the interior of society and reaching beyond its local place of birth to feed on an ever widening circle of nations with the establishment of military bases, gained through uninterrupted imperialist adventures — at once, gorging itself on the superfluous labor of society and expanding the scale of its production. With the increase in the productivity of labor resulting from Capital’s desire to maximize profits, an even more rapidly increasing portion of all economic activity fed this parasite on society. Millions of laborers who would otherwise be unemployable found positions in the State as functionaries, bureaucrats and paper-pushers of every conceivable sort — rivaled only by the domestic industry of advocates, lobbyists and frauds, who daily discover new threats, domestic or foreign to the national interest; new, previously unknown, social maladies that require urgent government intervention; new reasons to tax some substance or regulate it, or require a prescription for it, or jail those who use it; new reasons to raid the public coffers, shake down the taxpayer, or further expand the nation’s debt to the banking houses on Wall Street, and, of course, a massive cottage industry of defense, police, intelligence, and penal contractors, manufacturers, and support services.

As PunkJohnnyCash has pointed out the Capitalism versus Communism paradigm is as false and misleading as the Left-Right paradigm. Capitalism offers nothing to society but more of what I have described above, and communism has no positive vision of a new society: understood properly, and not in the caricature of the vulgar Marxist, “Philosophically,” states the French philosopher, Alain Badiou, “communism has a purely negative meaning.”

Marx, in his own words, simply described communism as an event — a revolutionary movement of society — an “alteration of men on a mass scale” … “in which, further, the proletariat rids itself of everything that still clings to it from its previous position in society.” He offered little on what society would look like in the aftermath of such an event beyond this:

Only at this stage does self-activity coincide with material life, which corresponds to the development of individuals into complete individuals and the casting-off of all natural limitations. The transformation of labour into self-activity corresponds to the transformation of the earlier limited intercourse into the intercourse of individuals as such. With the appropriation of the total productive forces through united individuals, private property comes to an end. Whilst previously in history a particular condition always appeared as accidental, now the isolation of individuals and the particular private gain of each man have themselves become accidental.

What would this society look like? To the ill-placed frustration of many, Marx never speculated on this question, only that this event marks both the ridding of the old “muck of ages”, and the founding of a new society. Moreover, he decidedly separated himself from those who constructed plans or schemes for a new society.

And, there is a reason for this: under the conditions described by Marx, there are no longer any external constraints — natural or man-made — on the actions of the individual. This would be true for two reasons: first, assuming sufficient development of the productivity of labor, we are freed from the requirement to work — which becomes a matter of personal preference, and, therefore, expresses only the innate human need to be productive and creative. On the other hand, with the end of unnecessary labor, the State is entirely discarded and replaced with the free, voluntary, association of individuals.

Under these circumstances, there are no necessary principles on which to found our relationships with other members of society — in the sense of a set of external economic or political laws or constraints on our activities and relationships — and, thus, no possible way of conceiving what society might look like in the aftermath of such an event.

Although I can be very wrong on this, what I have concluded from Marx’s writings on communism is this: far from being the anti-pole of capitalism, in the writing of Marx, at least, communism is not a “new society” that can be counter-posed to capitalism, as the Soviet Union was counter-posed to the United States as great powers during the Cold War, communism is, instead, the concluding event of capitalism itself — an event in which the members of society put an end to the State, Labor, and Capital; and replace them all with their voluntary association.

I am very eager to hear what others have to say on this.

Challenging The Paradigm: A reply to PunkJohnnyCash

In his thought provoking essay, Capitalism vs. Communism Challenging The Paradigm, I think PunkJohnnyCash has posed exactly the right question for our times:

Can the Capitalism vs. Communism paradigm be challenged just as so many of us have found the flaw in a left-right paradigm?

To my mind, this is the most important question of the year as it closes and we begin 2011.

What I have tried to argue in my posts, What help for the 99ers?, and on my blog for some time, is that the demand of the Left for the abolition of Capital and that of the Right for abolition of the State are the mirror forms of the same demand for the abolition of unnecessary Labor. Capital is a mode of production of surplus value based on the continuous extension of labor time beyond that duration necessary to satisfy human need. The State is nothing more than this same mass of superfluous labor time congealed into the form of a repressive, expansionist machinery of political, economic, legal and military coercion.

In economic terms, the State is the necessary companion of Capital, because it provides the types of superfluous expenditures which become increasingly important to Capital. As the mode of production achieves an extraordinary high level of development, the unprecedented productivity of labor itself becomes a barrier to profitable investment. The enormous and growing quantities of goods issuing from industry rests on the productive activity of an ever shrinking number of productively employed laborers. At the same time, an ever increasing mass of laborers are utterly cut off from any productive employment, and would be cut off from all employment were it not for the direct and indirect expenditures of the State.